Olive ValleySlow AgricultureLorenzo Autieri and Patrick Meyer

Despite great variety of agriculture in Peloponnese, two types of fruit cultivation dominate the landscape: oranges in Argos and Lakonia, and olives in Ilia and Messina. Tied to altitude and soil quality, the areas of specific cultivation (olive, orange, wine, etc) are clearly delineated in the landscape.

The word agriculture shares root with Greek “agrios”, meaning “wild”. A degree of unruliness is still part of agricultural production in Greece and in Peloponnese, due to small field sizes and small-scale individual producers, who often operate without formal land title. Compared to elsewhere in Europe the size of agricultural properties in Greece is exceedingly small: 4.4 hectares in average, being even smaller in Peloponnese. In Switzerland, despite the mountainous terrain and the small land subdivision, the average land property is 17.4 hectares. EU policies and subsides have decisive impact in regulating agricultural production in Greece; however, despite the fact that the EU allocates 2.5 billion euros in annual subsidies for production in the so called “less favoured areas” such as the small-scale production in Peloponnese, due to the poor state of local politics and administration, much investment is wasted.

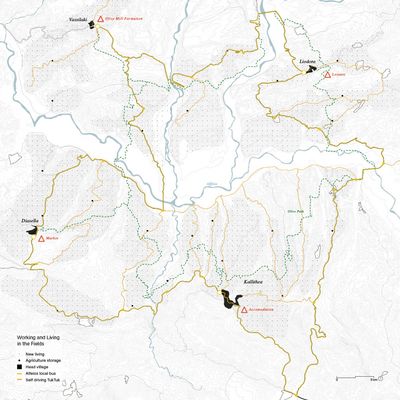

The Alfeios River valley and the surrounding hilly slopes covered with olive trees have served as the frame in this project to examine the transformation of olive landscapes in Peloponnese. Due to its hilly topography, the area is designated as “less favoured” for cultivation and receives EU subsidies.

Olives and olive oil are the most significant agricultural products in Greece, tightly connected to Greek cultural traditions, shaping both the Greek landscape and regional identities. The importance of olive farming is illustrated by the fact that municipal workers typically get time off every year for the olive harvest. Families in Greece, regardless whether “rural” or “urban”, continue to produce olive oil for themselves. Artisanship surrounding the olive industry stands now in sharp contrast to the industrialisation of agriculture in many parts of Europe. The traditional olive farming ecosystems have high levels of biodiversity due to the still-limited use of pesticides. On the other hand, it appears that for small-scale olive producers in is becoming increasingly difficult to adequately promote traditional farming methods and benefit from them.

Complementing the family labor, in Greece and Peloponnese the small-scale producers in agriculture have developed economic relationships with migrant workers. In reclaiming abandoned fields and century-old farms, migrant farmers now help revive Greek countryside. Beside foreign work migration, a new type of urban-to rural migration has emerged: more and more young professionals abandon large cities to move to the countryside, in response to increasing urban unemployment and the financial crisis. In addition, the potential of agro-tourism hasn’t yet been fully explored. Traditionally, agriculture in Greece has been an autonomous field of labor and production; its new association with leisure and tourism may still appear incompatible with the popular understanding of the “countryside.”

Climate, topography and other natural conditions and hazards, property rights, traditions, national and international economic policies and migrations, are all powerful forces shaping the olive production landscape in Greece. In Peloponnese, the predominance of family farms and cooperative organisation structures for olive oil processing and trade, emphasise the highly local character of olive agriculture.

The project aimed to describe transformation processes shaping the countryside of olive cultivation. Interested in the potentials of the small-scale, family-based production for the future of European countryside, the project envisions a new kind of “slow territory”, with new ways of living and working in the olive groves.