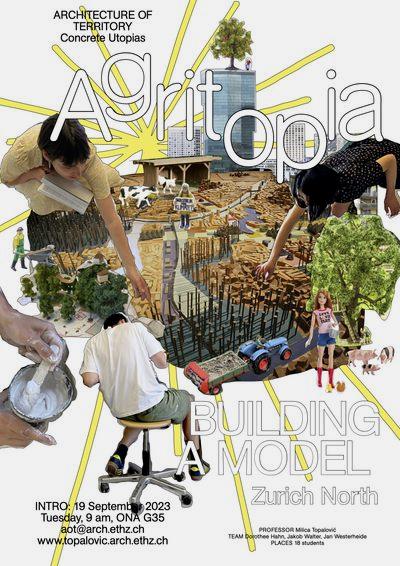

Agritopia

Building a Model for Zürich Nord

Be realistic, demand the impossible

—

During the summer weeks we used to prepare this semester, apocalyptic news of forest fires, migrant tragedies, and war, dominated the media. The manifold crises of climate change, biodiversity loss and increasing social inequity have left many disillusioned, while others are demanding prolongation the status quo through solutionism and technofixes. We lament the limits of Western democracies, state failures and the power of the Big Tech, but comprehensive action addressing the climate agenda is still lacking, in Switzerland and other countries. Some say that we have settled into a “long defeat” in which there is no room for optimism left. As designers we are always oriented toward the future; but, how to approach the future when our collective capacities to imagine and to act seem to be depleted? Younger generations today represented by activist movements like Fridays for Future, and others before them, have shown us that faith in a better world is necessary, if we are to move forward. As Henri Lefebvre put it, summarising the experiences of the 1968 movement: “In order to extend the possible, it is necessary to proclaim and desire the impossible. Action and strategy consist in making possible tomorrow what is impossible today.”

We thus recognise a need in our studios to “demand the impossible,” by exercising our collective imagination, to increase our capacity to act as designers, and tackle the causes of manifold crises. We are therefore initiating a new studio series Concrete Utopias, based on the notion Konkrete Utopie by philosopher Ernst Bloch, where we return the notion of utopia—not as a mere fantasy, but as a concrete potentiality of change grounded in the real, socio-economic and political conditions of a given context. Countless utopian projects continue to be proposed today, but to what ends? Think of the recent NEOM city in Saudi Arabia and the California Forever, illustrating the empty promises of consumerism and corporate governance. Countless others actions and initiatives have been realised as concrete utopias, showing potential for wider and far-reaching transformations based on democratic orientation and environmental agenda—like the Zone à défendre (ZAD) at Le Mormont, the Rote Fabrik in the city of Zurich, the Halen Estate by Atelier 5, the community project at Vrin, and community-based agriculture projects all around Switzerland. These and other examples have inspired shifts in the discourse and practice and led to positive change. Utopian thinking thus remains useful and necessary as a method to initiate change.

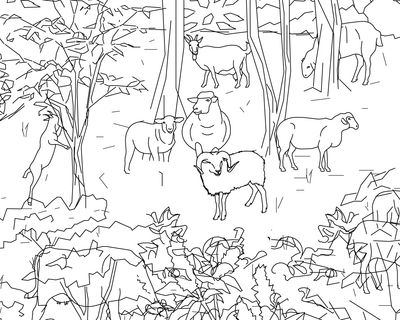

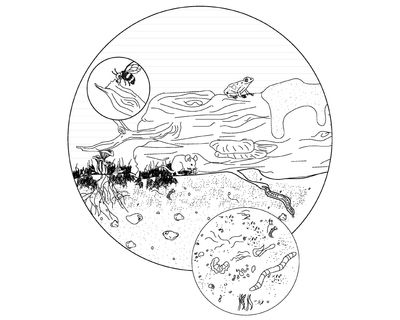

Our first concrete utopia will be an AGRITOPIA. The recurrent focus on agriculture in this studio is not accidental—we believe that the crisis of our imagination is reinforced by the separation of the urban and the rural in our culture, and by continuing to think the future only in terms of urban life disconnected from the land and nature. To imagine a different urban future for Zürich, we will work on agricultural territories that lie at the city’s edges. They are an example of periurban landscapes which form vital support to cities with water sources, clean air, various materials, land for food and energy production. Only by radically reimagining territorial organisation and land use practices in ways that are currently often disqualified as utopian and impossible, can we divert ongoing tendencies of agricultural intensification accompanied by soil degradation, water pollution and biodiversity loss. Designing sustainable biophysical relationships reflects in urban life itself, and will enable us to address issues of consumption, of commodification of land and labour, and even of housing crisis.

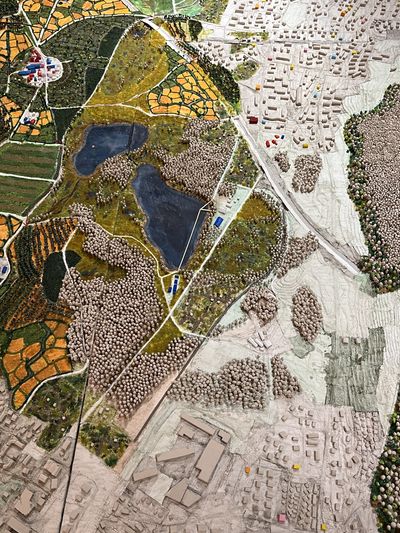

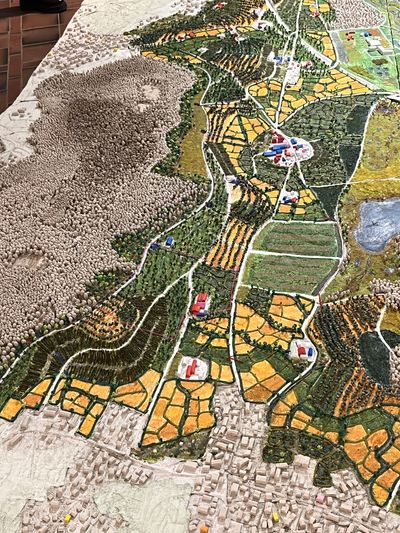

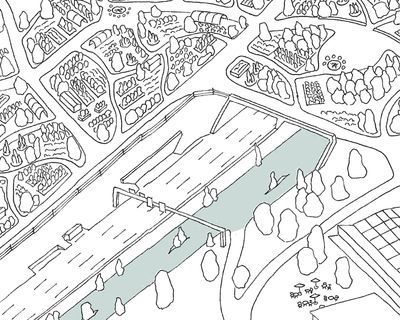

The place and time for AGRITOPIA are agricultural fields of Zürich Nord beyond 2050, in a world of future generations. A five-minute walk from our studio in Oerlikon toward the north, the city fabric stops and a view opens onto an agricultural landscape connecting the city of Zurich and the communes of Rümlang and Regensdorf, with Katzensee and its adjacent wetlands at its core.

This landscape is encircled by urban fabric, which stopped spreading, creating a new condition of large agricultural landscapes withing the city. The growing awareness of the need to preserve and protect non-built areas in the 1960s and 1970s in Switzerland among academics, planners and citizens paved the way for a number of decisive laws that built the legal framework for spatial planning and land use to this day. These laws are based on two different approaches: the protection of the non-built, such as nature reserves and agricultural land for food production, in particular the protection of crop rotation areas (Fruchtfolgeflächen) since the 1970s on the one hand, and the limitation of the built through the Raumplanungsgesetz (1979) and its revision in 2013, on the other. Today, the landscape between the City of Zurich and the communes of Rümlang and Regensdorf constitutes the largest non-built area in the immediate vicinity of Zurich’s centre, but without encompassing plans for its future use. Agricultural activities here vary from conventional farms, over organic farming, and community-supported agriculture, to Switzerland’s largest agricultural research facility Agroscope. In the studio, we will form groups to tackle specific topics and potentials of the site—from local food production and distribution, to future of agricultural work, the water and nature preservation, to cooperative organising and common ownership. We will develop a concrete agritopia based on close observation and analysis of the existing qualities of the landscape and the pioneering practices that make them possible.

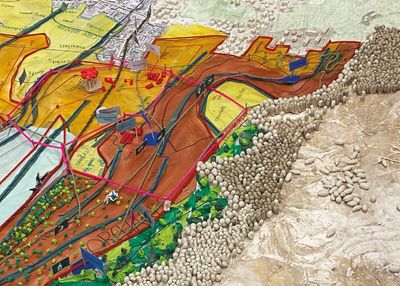

Large-scale models have been used, again and again, to negotiate and represent future visions of space and social organisation. Intuitive and suggestive, models prefigure a different reality and help imagine a possibility of moving from the here and now, to there and then. A large-scale model of the site in Zürich Nord (approx. 4 × 3m), will be the tool of our collective project—both our final result and our working tool throughout the semester. Our sparing partners in the process will be scientists, designers, policy makers, and farmers and activists currently working on site. We will work with diverse materials and techniques, and in a range of scales from 1:100 to 1: 2000, exploring and visualising relationships between human practice and the territory. A technique of narrative model-making, where we tell stories in 3-D by presenting future protagonists, events and places, will help us convey complex ideas of change, negotiate scenarios with each other, and bring others onboard.

CONCRETE UTOPIAS

Concrete Utopias (based on the notion of Konkrete Utopie by Ernst Bloch) is a studio series at Architecture of Territory dedicated to anticipatory, future-oriented and collective design projects exploring forms of building, territorial organisation and social reproduction based on social and environmental justice and equality, as alternative approaches addressing the manifold crises. The studio series is affiliated with the ETH EPFL MAS in Urban and Territorial Design. Citizens, experts, fellow designers and artists accompany us in the process.

PROCESS AND RESULTS

The semester consists of investigative journeys and intensive studio sessions. Architecture of Territory values intellectual curiosity, commitment and team spirit. We are looking for avid travellers, motivated to make strong and independent contributions. Students will apply a range of methods and sources pertaining to territory, including ethnographic fieldwork, large-scale drawing techniques, model making, literature research, essay writing, and online publishing. Students work in groups of 2 to 3.

FIELDWORK

Investigative fieldwork is a crucial part of the project. During common days in the field in Zürich Nord agricultural pioneers and experts will guide us through the territory, including visits to several hamlets, farms and community farming projects. Throughout the semester, students will also conduct independent fieldwork in the respective student groups, exploring and documenting the landscape, and interviewing locals and experts.