AtlasData SovereigntyEsma Alili, Timo Feddern, Joanna Druey, and Valentin Egger

Switzerland aims for digital sovereignty and its people entrust their government with that responsibility, as confirmed with the recent approval of the E-ID act. The state categorises data into four stages of sensitivity and protects them accordingly. A certain interdependence with hyperscalers remains, which is mitigated through colocation, a type of data centre where equipment, space, and bandwidth are available for rental to retail customers. Swiss Fort Knox is the physical embodiment of data protection, the peak of digital sovereignty. Being located in a former military bunker in Saanen (BE), it intends to offer protection even against geopolitical threats. While private actors are crucial to shape the digital landscape and future of Switzerland, the Confederation directs the ecosystem according to the public interest and preserves digital sovereignty.

E-ID(entity) in Your Pocket

E-ID in Switzerland

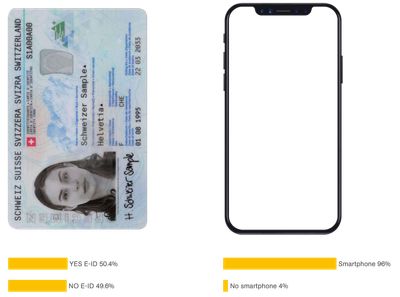

On September 28th, 2025, the Swiss population accepted the Federal Act on having an E-ID to be issued and managed by the State. While 96 % of the population has a smartphone and is therefore directly affected when it comes to data security and privacy policies, the act just barely got accepted by the Swiss population with 50.39 % yes votes and 49.61 % no votes. Refusing the act would have resulted in private actors having to fill the demand of an E-ID. The State would not have been able to account for privacy policies and data security.

However, the acceptance of the Federal Act reassures that the Swiss people want to entrust its E-ID to the state only and maintain sovereignty thereby.

Data Sovereignty and Digital Sovereignty

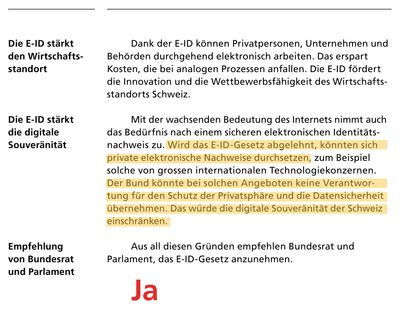

Digital sovereignty is one umbrella term of data sovereignty amongst others. For any topic to enter into the domain of digital sovereignty three areas must be touched: the digital sphere, the territory and the statehood. The term therefore covers digital process operations which have an impact on the territory of Switzerland and its institutions (statehood). Especially, the term statehood foresees that the state as an institution must not be threatened to maintain the states digital sovereignty. If the Swiss government loses data such as the Avalanche Prediction Software, the digital and territorial aspects may be affected. However, Switzerland as an institution is not threatened and therefore its digital sovereignty is also not threatened.

The Inevitable International Part in the Swiss Cloud Strategy

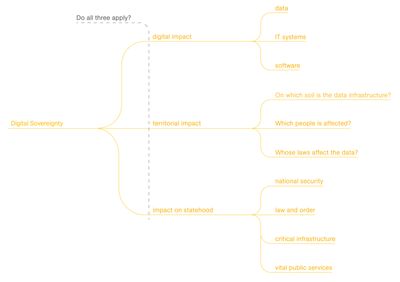

In order to maintain digital sovereignty, the Confederation developed a strategy which classifies data into four stages. They are categorised according to sensitivity and respective level of protection.

Stage I

DATA CENTRES IN EUROPE UNDER CONTRACT WITH FEDERATION

The map shows the data centre locations within Europe where the Stage I data may be stored. The locations of the following cloud providers are shown: Oracle, Alibaba Cloud, Microsoft Azure, Amazon Web Services (AWS) and International Business Machines cooperation (IBM). Source: unknown. Scheme: Joanna Druey, 2025.

Oracle Data Region

Oracle Data Region Alibaba Cloud Data Center

Alibaba Cloud Data Center Microsoft Data Region

Microsoft Data Region Amazon Web Services Data Region

Amazon Web Services Data Region IBM Data Region

IBM Data Region

The first stage regards intern and non-classified data such as data from swisstopo Base Maps which will be stored in the public cloud. The Stage I data is purely non-sensitive such as data of weather measurements. These data are stored outside of Switzerland in Ireland but are encrypted as they leave Switzerland. The weather forecast of Switzerland does travel to Ireland, yet nobody can read it without passing through the Swiss data warehouse in Zurich.

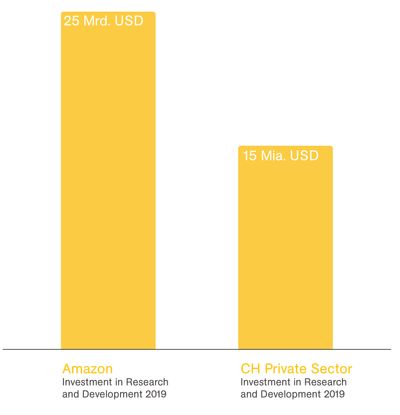

The government has made contracts in the year 2023 with five international cloud providers such as Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and others. Making these contracts caused media and political outrage. However, having own data centres would be difficult to implement. On one hand, data quantity fluctuates quickly. It would take up to fifteen years to build a data centre while renting as much space as needed with international providers requires only minutes. On the other hand, it would be unreasonable financially for Switzerland to invest in data centres. Amazon Web Services alone invests 25 billions US dollars in research and development. This sum is ten billions more investment in research and development than the whole Swiss private sector across all domains. The financial divergence is clear. The statistics show the capacity of hyperscalers compared to Switzerlands investment capacity.

Stage II

(SEMI-)PUBLIC DATA CENTRES IN SWITZERLAND

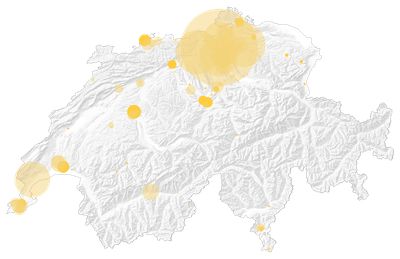

The map shows the concentration of data centers in Switzerland. Furthermore, it shows that there is a concentration of data centres in Zurich, where for instance Microsoft Azure data centers are located. Other data centres accumulate throughout the western part of Switzerland such as Geneva or Bern. Source: Modified Studio Resources, 2025. Modification: Joanna Druey, 2025.

- Public Data Center

- Semi-Public Data Center

Stage II of the cloud strategy regards the non-classified or intern data. The stage II data have specific requirements to be stored within Switzerland, such as certain non-confidential health data. These data will also be stored with Amazon Web Services, Microsoft, or other international providers as mentioned above. In contrast to Stage I, these data will be stored in Switzerland at colocations of the external providers.

Stage III and Stage IV

FEDERAL DATA CENTRES SWITZERLAND

The map shows the locations of Federal data centres in Switzerland. Campus (Frauenfeld, TG), Primus (Bern, BE), Comes (Bern, BE). Furthermore, it visualises the potential locations of other military data centres. As the map showcases, these data centres could be in the alpine territories throughout Switzerland. Source: Studio Resources, 2025. Modified: Joanna Druey, 2025.

- Potential Location of Swiss Military Data Center

- Federal Data Center

Stage III and stage IV can contain non-classified data and intern data as well. In addition, they regard confidential, system critical and secret data. These data are stored within federal data centres. Those data centres are utterly secure. Nonetheless, they are vulnerable towards geopolitical threats.

There are potentially three military data centres in bunkers in the Swiss alpine territories. These bunker data centres are most likely built similar to the case study data centre Swiss Fort Knox. Military data centres are of utmost importance to guarantee digital sovereignty in times of conflict as they can provide security even against nuclear threats.

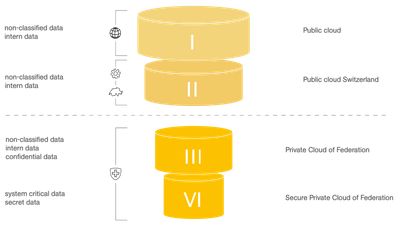

The Swiss Government Cloud

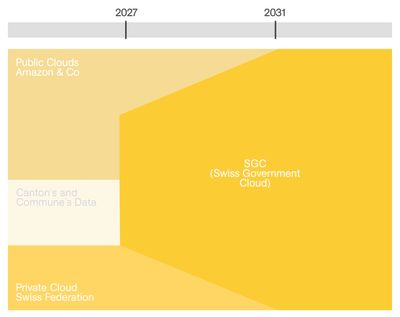

Source: admin.ch, 2025. Modification: Joanna Druey, 2025.

Government data is currently stored in public clouds run by international providers. Switzerland plans to introduce the Swiss Government Cloud (SGC). This would allow Switzerland to regain control over their data and ensure data sovereignty. Moreover and more importantly, the SGC would allow Switzerland to have a unified user platform across all their competencies. The aim is to own and manage the own data. The first data migration is planned to take place in the year 2027. By 2031 the data migration is to be concluded.

The SGC will still use data centres from major hyperscalers but under the principle of colocation. This means that Switzerland wants to use own servers and softwares instead of the ones provided by hyperscalers.

Colocation Explained

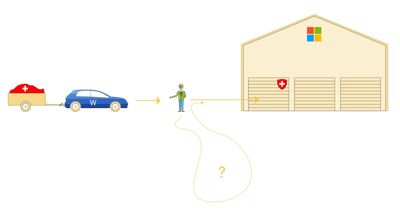

Scheme: Joanna Druey, 2025.

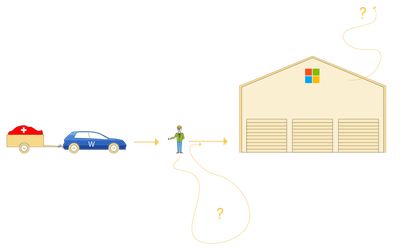

To understand colocation the analogy of a garage will be used.

The trailer carries the Swiss data, the car is the software with which the data was created and transferred. In this case the software is Microsoft Word. The cloud provider, or garage, is in this specific case from Microsoft as well, but it could have been any of the above mentioned cloud providers, such as AWS, Oracle, or the like.

Once the trailer is handed over to the parking attendant, the data trailer will be stored at Microsoft’s garage. However, it could be that the parking attendant takes the trailer for a spin (giving data to third parties) or looking at what it’s carrying. Furthermore, storing the trailer in the garage that Microsoft provides and owns, still leaves the risk that Microsoft may handle it unrightfully, treat and store it unencrypted, or move the contents of it to somewhere else.

Scheme: Joanna Druey, 2025.

In the second scenario Switzerland buys a garage at Microsoft. Thereby, we have to cross through the hallways (in this case fiber connections) to the garage, but we are the only ones having a key and access to it. Yet, the car is a software—in this case Word—which is not created or controlled by Switzerland. The parking attendant would have to park the trailer in the Swiss garage at Microsoft. Still, there could be the possibility to take the car for a stroll or a look inside. Data security, control, and sovereignty would be still at risk.

Scheme: Joanna Druey, 2025.

The third and most secure scenario would be that Switzerland not only owns a garage at Microsoft but it also provides a Swiss car which means a Swiss software that carries the trailer safely without the risk that someone else might get involved. The Swiss trailer would be parked directly into the Swiss garage with the Swiss car.

Even though it is the most secure way towards digital sovereignty, the difficulty arises at the level of implementation since people rather use Word than a Swiss software alternative like LibreOffice.

Nevertheless, this strategy has been adopted by numerous institutions worldwide, such as the Austrian Army, as well as other European municipalities and companies such as the German state Schleswig Holstein, the French city Lyon, or the Dutch government through introducing the data sovereignty supporting software LibreOffice.

The Peak of Digital Security

Physical Security: an Overview

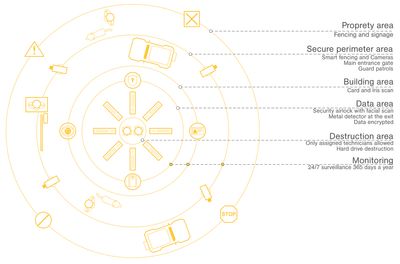

Scheme: Valentin Egger, 2025.

Physical security concepts for protected buildings, in this case data centres, start with spatial boundaries, separating public from private land through fences and signage to create a securised “inner” space. This inner— and controlled—space, also called the “secure perimeter” is being controlled by patrolling personnel (depending on the object they might be supported by cars, dogs, etc…) supported by hard- and software such as cameras, motion detectors, smart sensors, and so on.

Within these secure perimeters the actual “object of interest,” for example a data centre, resides. Access to these buildings is usually possible through doors (either small ones for personnel or large ones that also allow access by vehicles for deliveries or pickups). These entries are surveilled by cameras and access is only possible with a badge, iris or fingerprint scan and other verification methods (for example a manual search of a car or truck) to authenticate and authorise users. This should also include the verification of a person’s tasks and its access needed for it (this might also include a “bodyguard” to enforce a four-eye principal on what happens within this building or an area of it).

The destruction area refers to the area where the hard disks are destroyed. It is important to acknowledge that data centres offer areas for customers to destroy their hard drives in case they want certain data to disappear without the risk of losing them, having them stolen, or copied. Therefore, the destruction area is only accessible for assigned technicians.

Within the following “entry-area” of a building there is a monitoring area, used for verification and strict surveillance of people. Sometimes this includes airport-like scanners for personnel and baggage to keep out any dangerous devices or software. The final access is then again a door (usually a very thick and secure one) with badge or biometrical readers, a man lock, and other security measures to ensure that only allowed technicians and customers can enter the final “server-area” of the data centres. There might be multiple nested security areas like this one to ensure an even finer separation of customers and employees.

Swiss Fort Knox

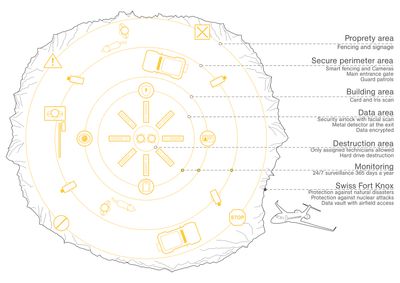

Scheme: Valentin Egger, 2025.

Swiss Fort Knox, owned by Mount10, is located in Saanen, in the Canton of Bern. Due to its territorial conditions this data centre includes even more security measures compared to a classical “above-ground” data centre, by providing direct access via its own airport. Additionally, due to its location within a bunker it is less exposed to aerial and local attacks and is self-supplied with power, water, or other important goods for the data centre for multiple days or weeks. This is comparable to Swiss “Stage IV” data centres which are built and maintained for the Swiss military and government to store and process information also during war times where the physical and digital security of publicly placed data centres cannot be trusted anymore.

Source: Valentin Egger, 2025.

Sovereignty on the Radar

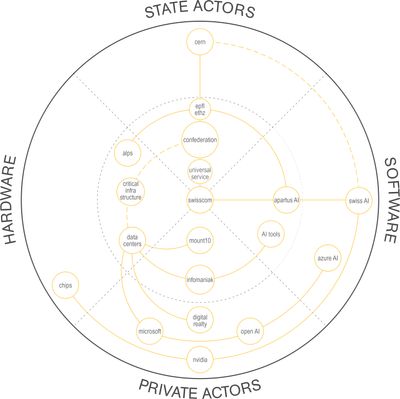

Having gained an understanding of how the Swiss Confederation manages and protects its data, this section focuses on the connections between the various actors that make up the Swiss digital landscape.

It is important to identify the public and private actors and their actions in the software and hardware domains.

Public Actors

First, as the main stakeholder of Swiss sovereignty, the Confederation must ensure that a basic telecommunication service is available to the entire population and in all regions of the country. This universal service was delegated in 2023 to Swisscom, the largest telecommunications operator in Switzerland. The semi-private company has been offering an AI platform that facilitates access to and the use of AI models for Swiss companies since 2024.

To encourage AI innovation and sovereignty, the Confederation supports and funds the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology. For this purpose, EPFL and ETH Zurich have access to public infrastructures such as the Alps supercomputer in Lugano.

The computing power of the supercomputer has allowed these institutions to develop a large-scale open model named Apertus, which is intended to reflect Swiss values of transparency, multilingualism, and responsibility. This model is made available via Swisscom’s platform.

Moreover, Swiss public institutions also collaborate with European scientific bodies such as the CERN (Conseil européen pour la recherche nucléaire). While CERN is not a direct partner of the Swiss AI Platform, it partly benefits from it and contributes within the scope of its research.

Private Actors

International private actors play an important role in Switzerland’s digital ecosystem. Amongst them most important stakeholder remains the company NVIDIA.

NVIDIA is the world leader in making and providing the chips necessary for training and running large artificial intelligence models. The American company is a partner of Swisscom on the AI platform.

Other private actors include Swiss companies which compete with Swisscom such as Infomaniak. The Swiss tech company offers a platform of sovereign AI tools as well, ensuring that data which is produced in Switzerland is also hosted in Swiss data centres.

OpenAI recognised the concern of data sovereignty. Thereupon, it partnered with microsoft for their AI model Azure. That way Swiss data resides in Switzerland as well. The same strategy is adopted by other international and nationwide private actors, such as Digital Realty and Mount10, which is the owner of the alpine bunker data centre Swiss Fort Knox.

The Confederation defines a list of critical infrastructures, considered essential for the proper functioning of Switzerland. Private actors that host sensitive state data or other critical information benefit from logistical and regulatory support from the government.

Conclusion

Data sovereignty concerns everyone who has a smartphone. While the majority in Switzerland is affected, the Swiss population narrowly accepted the federal act on having an E-ID. On a governmental level there are strategies that are meant to lead Switzerland towards digital sovereignty. However, a certain interdependency already exists with and within the tech-ecosystem, intertwined between private and public stakeholders. Considering geopolitical tensions, spatial aspects, and Switzerland’s reputation and identity as a secure island in the heart of Europe, the country remains unthreatened in the era of intelligence and AI. Mount10 embodies the peak of security with their data centre Swiss Fort Knox being located in a former military bunker in the Swiss alps. Between the love-hate relationship towards the tech-industry, the entanglement of private and public actors and geopolitical tensions, the question remains how much sovereignty can be promised and if the world’s most secure data centre Swiss Fort Knox sets an example for future data centre designs or if it is just a seized opportunity in favor of Mount10 and their marketing strategy of Swiss Fort Knox.