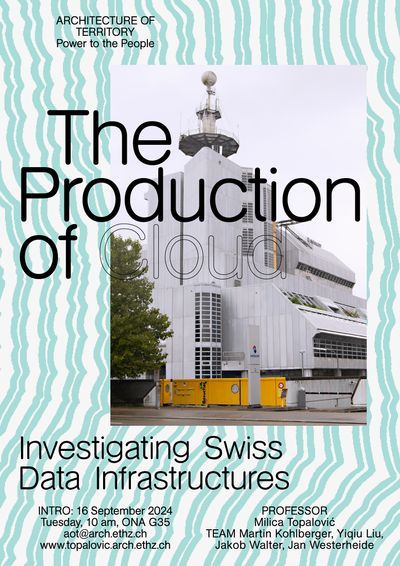

The Production of Cloud

Investigating Swiss Data Infrastructures

Your TikTok scroll, a robotaxi’s U-turn, a question to ChatGPT—every byte lives somewhere in the cloud, consuming megawatts, and silently redrawing the space around us. Public discourse, however, surrounds us with cloud-like images against bright blue skies. Artificial Intelligence—the latest and most attention-hungry use of cloud computing—has been adopted by more than half the world’s population. Yet, the production of the cloud relies on material processes—a planetary metabolism of mineral extraction, water depletion, e-waste, and often exploitative labour practices in remote regions. Every click, search, or generated image drives the global AI race for better models, larger infrastructures, and tighter control over resources and data sources—so much so that AI is becoming an obstacle to energy transition. Alongside concerns such as digital pollution and digital detox, a debate on data sovereignty has emerged—it’s about the ability of nations, and thus institutions and individuals within their borders, to maintain local control over the data they produce, a form of power now increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few tech giants.

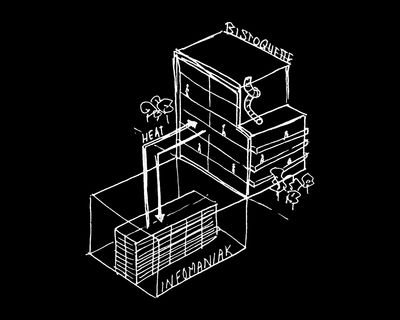

To understand AI’s spatial impacts, we will look at Switzerland—a country where “Data is the new gold”, and where AI growth capitalises on political stability, good infrastructure and low taxes. New data centres are being built in tax havens, along infrastructure corridors, near tech headquarters, and Zurich and Geneva’s financial hubs. Though the first Swiss data centres were built in the 1960s and the ‘70s by public institutions including the Swiss Military (EMD) and ETH, they were rarely given a distinct architectural expression. The iconic building of the Swisscom data centre, designed by Theo Hotz and built in 1979 as a PTT telecommunications hub, has been repurposed several times following technological shifts. Originally, it had a canteen, a Hort, and tennis courts for employees — all of which are no longer in use, since operations now require fewer than ten staff across the entire site. The history of the data centre is thus entangled with automation and a certain dehumanisation. As an architectural typology, data centres are often black boxes: hermetic, windowless, sometimes hidden in Alpine bunkers. Their architectural task is to maintain uninterrupted power supply, optimal humidity and temperature for server operations, and to articulate security barriers that restrict public access to both the facilities and information. These interiors are encased within defensive ensembles of fences, gates and security cameras—the amplified security aesthetics that arguably function as part of the business offering to private clients. In urban contexts, the location of a data centre is determined primarily by connectivity to the electrical grid and fibre-optic backbones. A recent study forecasts that by 2030, Swiss data centres will multiply and consume 15 percent of the nation’s electricity. In contrast, they provide few jobs, limited public benefits, and attract little investment to local communes. Although the Canton Zurich requires all newly built data centres to channel their waste heat into district heating networks, these systems are often already supplied from other sources or would require costly expansion to store and transmit the additional energy.

This semester, we invite you to explore the environmental and social impact of the Swiss data cloud. How can we study securitized spaces of minimal human presence? What kind of buildings and infrastructures underpin the cloud? What externalities does it produce and how might they be minimised? What forms of cloud expansion are expected in Switzerland? Who controls the use of data? We also want to speculate about a design of future data centres that are not merely black boxes but can serve as public assets. How might designing data centres contribute better to a just transition and to urban life? Each student team will be assigned a specific data centre in Switzerland as a study site to investigate through fieldwork and interviews. You will work across scales and media: from visualising Switzerland’s cloud infrastructures through narrative cartographies, to analysing urban impact of data centres through drawings and video and exploring their architecture through models. For your final project, you will build an interpretative architectural model of a data centre that expresses your design hypothesis. How can we make the invisible visible—and design a better data centre?

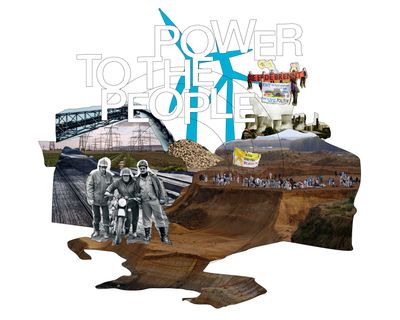

POWER TO THE PEOPLE

is a studio series at Architecture of Territory dedicated to improving the social and environmental outcomes of sustainability transitions. The studio is affiliated with the Swiss Network for International Studies (SNIS) through the research grant: “The Production of Cloud”.

PROCESS AND RESULTS

The work consists of investigative journeys and intensive studio sessions. Architecture of Territory values intellectual curiosity, commitment, and team spirit. We are looking for avid travellers and team workers, motivated to make strong and independent contributions. Our approach enables students to explore a range of methods pertaining to territory, including ethnographic fieldwork, drawing techniques, writing, videography, and online publishing. Experts and guests will guide us on that journey. Students work in groups of two to three. The semester is structured in three phases: 1) mapping and fieldwork; 2) urban analysis and video reportage; and 3) architectural analysis and model.

Core Course: MY CLOUD

Running parallel to the design studio, the core course MY CLOUD is a lecture series that aims to puncture the gaseous metaphor of “the cloud.” The series features four distinguished guest speakers—Flora Mary Bartlett, Marina Otero Verzier, Alfredo Thiermann, and Yiqiu Liu—from the fields of urban geography, digital economy, sociology, environmental history, and speculative design. Together, we will explore the cloud’s physical footprint, examine who owns and governs it, historicize the infrastructures that enabled its rise, and reimagine the futures it might create.

CREDITS

The semester offers a total of 17 credit points: the Design Studio 14 KP and the Integrated Discipline (Planning) 3 KP. The core course MY CLOUD offers additional 2 KP.