AtlasNetworks: Data BackbonesGabriele Clarelli, Ellen Stettler, Laurin Fravi, and Giovanni Paolo Valota

This research project examines the material and territorial networks laying the foundation of Switzerland’s digital infrastructure. What appears as a smooth, frictionless, dematerialised connectivity is in fact made possible by dense territorial infrastructures as fibre optic cables, data centres. And, ducts, as well as human labour building and maintaining them. By following these ‘'inconspicuous infrastructures,’' from the fibre-to-the-home connection (FTTH) to transcontinental submarine cables this research shows how digital communication is deeply rooted in physical space, shaped by public infrastructure, and geopolitical power. In Switzerland, the fibre optic network runs along other infrastructural systems and follows territorial logics inscribed into the ground. It links to global routes increasingly dominated by a few tech corporations, continuing patterns of techno-nationalist and colonial objectives. Through mapping and documenting, the project aims to surface the infrastructures and relations that sustain the Swiss cloud. It further examines how national narratives of innovation, neutrality, and the race for AI are maintained through technology, focusing on institutions such as ETH Zurich and the Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS).

Inconspicuous Infrastructures

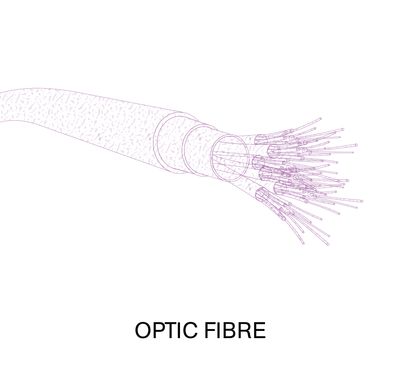

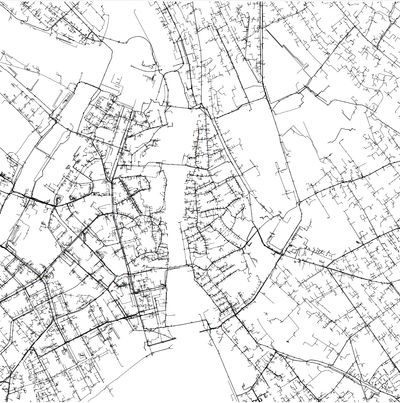

In order to understand how data flows function, an analysis of the material infrastructures that cross our territories is necessary. The things we see and interact with, our computers and smartphones, rely on an assemblage of material-technological objects and human labour along a multilayer supply chain. The way these items are put in relation to each other is what is described here as inconspicuous infrastructures. Placing the material technological objects at the centre of our analysis is an effort to de-hierarchise the understanding of digital spaces and architectures as immaterial and complex and therefore often out of reach of societal discourse. This often intentionally constructed over-complication has been theorised as a tactic of states and more recently tech-imperialists. Following the definition of Presner et al. the method of cataloguing entails a mapping that is an “on-going process of picturing, symbolising, contesting, re-narrating, re-symbolising, erasing and re-inscribing a set of relations.” This process renders visible scaleless objects that as a system create the grounds for other objects to operate on. The system of core interest here is the Swiss fibre optic network, its relationship with, and dependency on other infrastructures, its global connectedness, and the power that lies in the infrastructure.

Surfacing the Subordinate

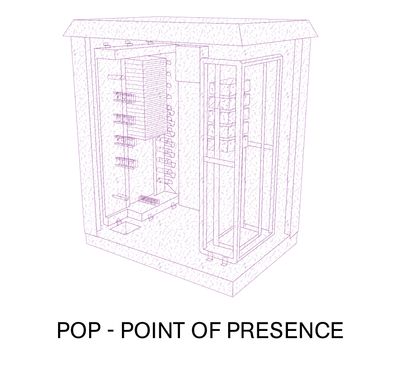

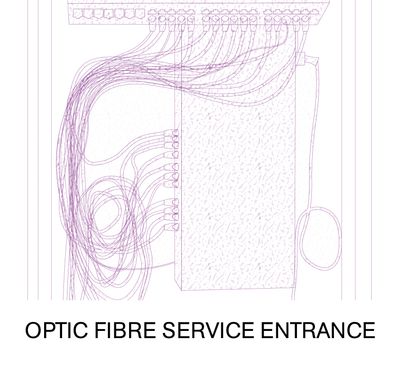

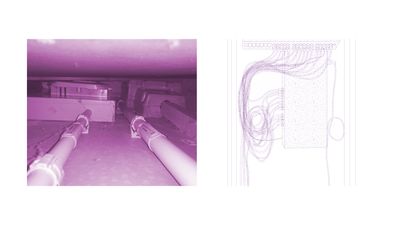

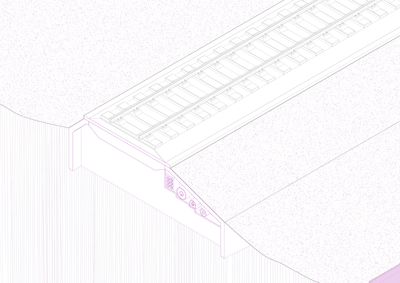

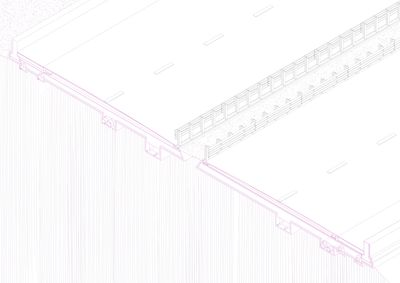

The house connection marks the transition between public and private domains. It is where the fibre optic cables that run below the street and along public ducts enters the building and where the abstract flow of light pulses is spliced into private domestic data flows. In Switzerland, Swisscom is the largest fibre optic provider, aiming to connect 75-80 % of homes and businesses by 2030.

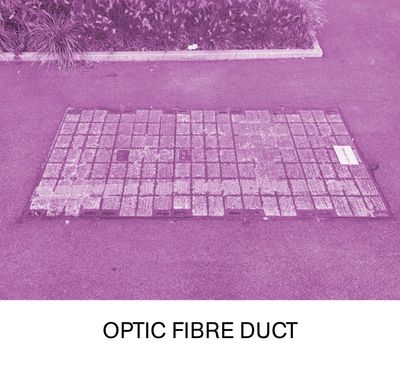

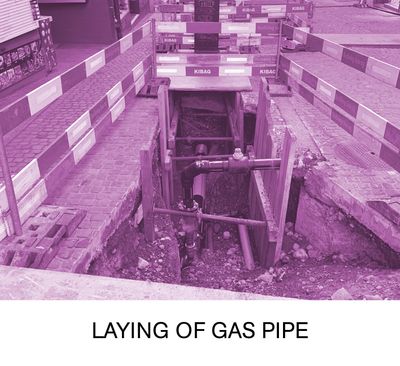

Shifting attention to the level of the street, the seamlessness of digital communication is deconstructed into a complex assemblage of infrastructure and labour. The intricate network system results from physical effort and ongoing negotiations.

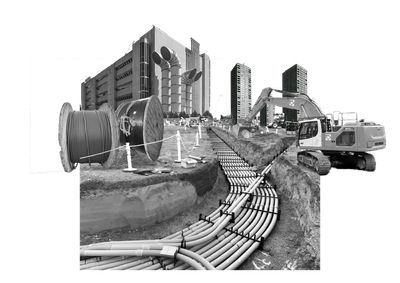

The construction of this network reveals the profound material entanglements of digital infrastructures. Streets are excavated by machinery, while fibres are carefully laid into trenches and covered up by workers. This process of revealing the underlying work emphasises the physicality of the digital. Even if only temporarily, its presence can be traced through excavation sites and the anonymous efforts of technicians and construction workers.

As data flows at the speed of light, infrastructure progresses at the pace of human labour and bureaucratic negotiations. This discrepancy between the velocity of signals and the inertia of construction is not a failure; rather, it is an integral part of the system. It serves as a reminder that the digital realm is always rooted in the physical, reliant on soil, concrete, copper, glass, and the social infrastructures that maintain, construct, and repair them.

Territorial Dependencies

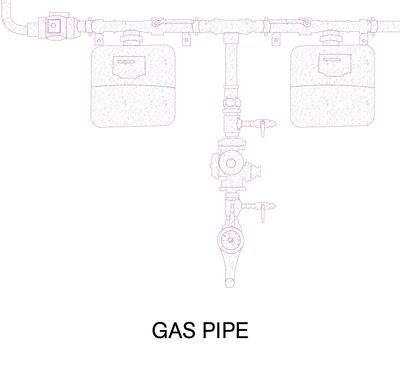

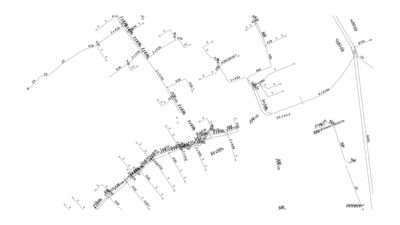

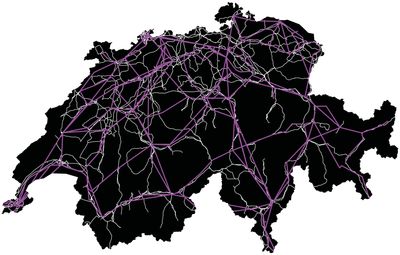

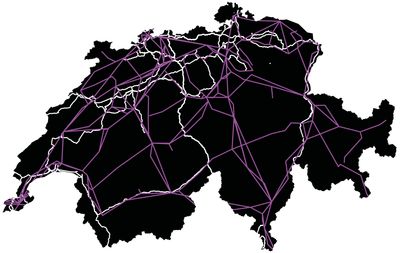

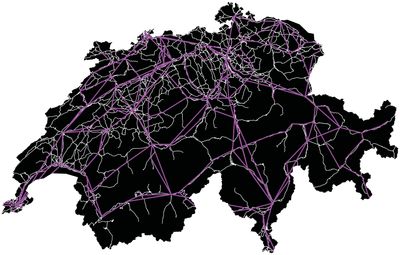

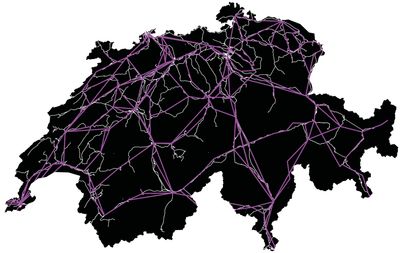

In Switzerland, the territorial dependence on infrastructures is notably evident. By comparing the layout of public infrastructure—such as the electricity network, gas pipelines, highways, or railway lines—with that of the fibre optic network, territorial parallels emerge. When examining a road section, there are guidelines governing where the various utilities are to be placed. The relationship between infrastructures is literally inscribed into the ground.

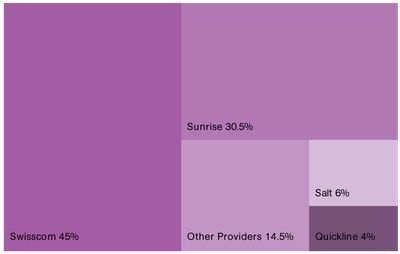

Swisscom dominates the fibre optic network, holding the highest market share as a semi-public entity. Following Swisscom are Sunrise, Salt and Quickline, which are all private companies that depend on public infrastructure, such as the electricity supply, public spaces and streets. This framework creates a partially public-funded profitability model, yet the specifics regarding the network’s positioning and territorial influence remain undisclosed to the public.

Considering these complexities, the Federal Office of Communications (OFCOM) initiated a roundtable in 2012 to coordinate the development of the fibre optic network and FTTH (fibre to the home) in Switzerland. This initiative seeks to prevent market monopolies, and discrepancies in technical standards.

Imperial Continuums

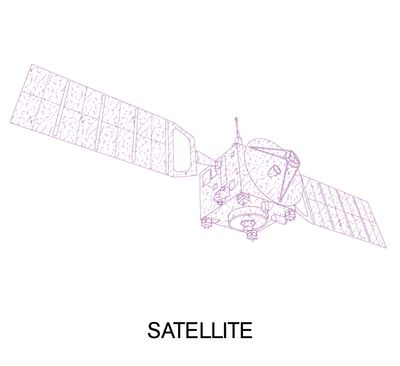

The Swiss network extends beyond national borders, connecting to transcontinental coastal nodes such as Marseille and Bilbao. Here, terrestrial fibres merge with a dense congregation of submarine cables linking Europe to Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas. The apparent self-containment of the national network dissolves into shared vulnerabilities and geopolitical interdependencies.

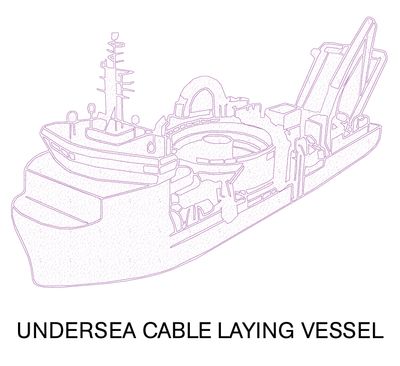

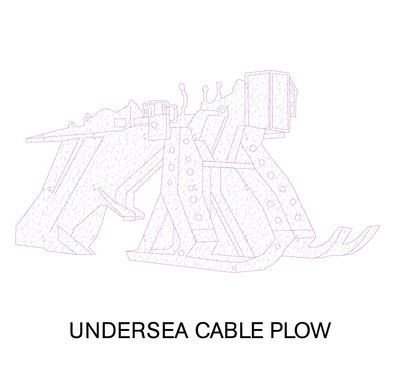

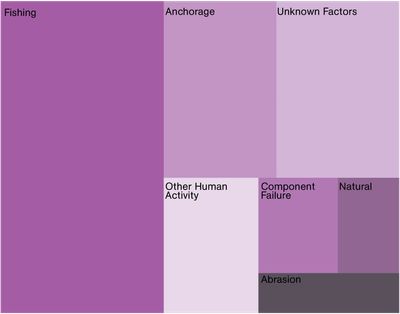

Within these geopolitical dependencies, a few global players maintain significant power and continue to expand this influence through an imperial-colonial logic. The overwhelming majority of global internet traffic traverses a network of submarine cables, which serve as the true backbone of global connectivity. The infrastructural scale becomes evident in construction efforts, with cable-laying vessels traversing the oceans to install new cables and repair damaged ones. Damages typically result from fishing activities or anchorage. Thanks to redundancies, failures of individual cables almost never lead to extensive outages; most of the time, only a slight latency is noticeable following an incident.

Nevertheless, submarine cables, cable repair ships, and cable landing stations have consistently been deemed legitimate military targets according to state practice and international law. Numerous instances of confirmed and alleged sabotage have heightened alertness and political tensions on a geopolitical scale. The laying, ownership, and utilisation of submarine cables have also become significant state interests, with disputes—such as those between the United States and the Chinese Government—leaving smaller territories in the Pacific caught in the middle of a play for power.

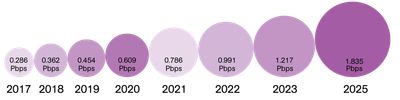

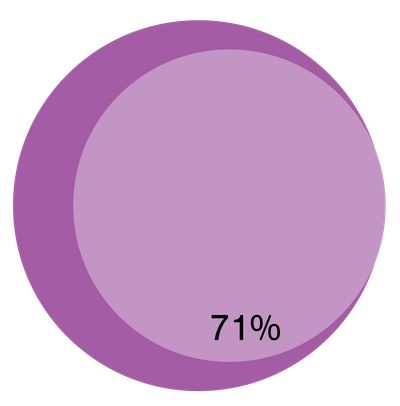

For long, submarine cables have been owned by various national telecom carriers. Beginning in the 1990s, entrepreneurial companies also entered the market. Recently, significant shifts have occurred, with large corporations involved in the construction of cables. Content providers such as Google, Meta, Microsoft, or Amazon are investing heavily in new cables, having outpaced internet backbone operators in recent years. Not only are these hyperscalers engaged in building the cables, but they also represent the primary source of demand for international bandwidth, accounting for 70 % of all utilised international capacity in 2022 (Burdett et al., 2024).

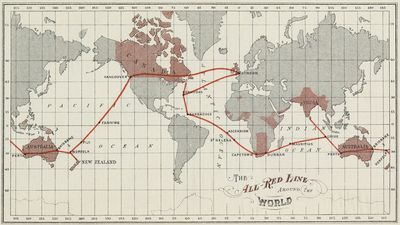

The rapid expansion, accumulation, and concentration of infrastructure in the hands of a few US companies are altering global power dynamics and forging transnational monopolies. This concentration does not merely encompass control over infrastructures; it entails a concentration of economic power, resource extraction, and data domination, alongside epistemic domination. Parallels with past colonial empires are evident. The first undersea telegraph cables were laid by the British Empire. According to a secret memo from the Imperial Defence Committee in 1910, “The maintenance of submarine cable communications throughout the world in time of war is of the highest strategic and commercial interests of every portion of the British Empire.” The most striking example is the system known as the “All Red Line,” which connected the colonised territories of the United Kingdom and enforced control. Maps from that era frequently depicted the British Empire in red, with a red line connecting those territories. As argued above, backbone networks have long been understood as imperial and nationalist projects.

Swiss Techno-Nationalism

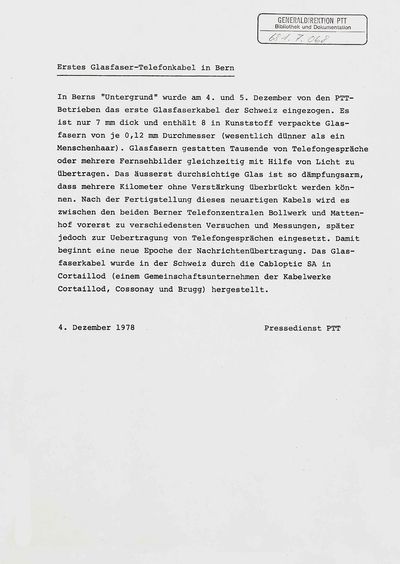

The introduction the fibre optic network in the late 1970s marked a new technological era. In December 1978, the PTT (Post, Telephone and Telegraph) proudly announced the installation of the first Swiss fibre optic cable beneath the streets of Bern. The press release, written in the bureaucratic tone typical for a technical milestone, nonetheless conveyed an undertone of collective pride: a “new epoch of communication” was beginning, driven by Swiss innovation, precision, and reliability.

This document illustrates how technological infrastructure became woven into the national narrative. The cable, modest in material—only a few millimetres thick and spanning just a few hundred metres—was contrasted with a symbolic magnitude, reinforcing the image of Switzerland as a leader in technology.

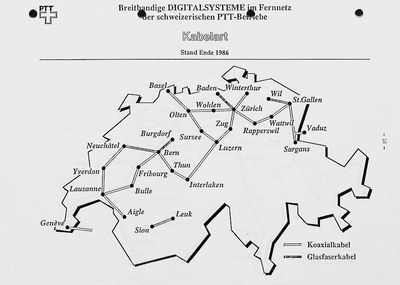

Eight years later, in 1986, a map reveals the Swiss PTT’s web of coaxial and fibre optic cables connecting the country’s main cities. The network appears evenly distributed, reaching every linguistic region. It visualises territorial coherence through infrastructure and serves as an expression of Swiss Technonationalism—the belief that technological infrastructure can embody and sustain national identity. Through this lens, Switzerland envisioned itself as both an island and a bridge, further strengthening its notion of neutrality.

This celebration of fibre optics as a nationwide achievement anticipates the contemporary rhetoric surrounding high-performance computing.

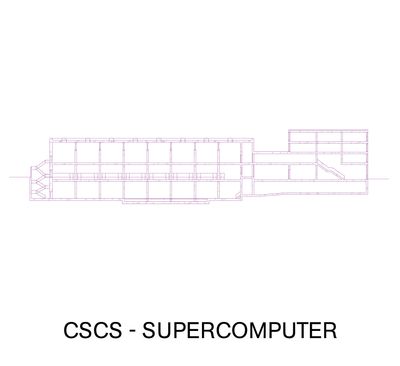

This celebration of the fibre optic network as a nationwide achievement anticipates the contemporary rhetoric surrounding high-performance computing. The Swiss National Supercomputing Centre (CSCS) in Lugano, which serves as the focal point for further research on this topic, is operated by ETH Zurich and holds a similarly symbolic function today: a promise that Switzerland will not be left behind in the accelerating race for technological advancement. The CSCS is often portrayed not merely as a scientific resource, but as a strategic safeguard. Beneath this rhetoric lies a subtle anxiety about being outpaced. This discourse of innovation has shifted from the notion of progress to a pressing need for competitiveness. Thus, ETH Zurich and CSCS become instruments in the race for AI, competitors in technological development, and operators within a global, imperialistic system.